HSE Scientists Reveal How Staying at Alma Mater Can Affect Early-Career Researchers

Many early-career scientists continue their academic careers at the same university where they studied, a practice known as academic inbreeding. A researcher at the HSE Institute of Education analysed the impact of academic inbreeding on publication activity in the natural sciences and mathematics. The study found that the impact is ambiguous and depends on various factors, including the university's geographical location, its financial resources, and the state of the regional academic employment market. A paper with the study findings has been published in Research Policy.

In Russia, nearly half of all PhD holders continue working at the same university where they earned their degree—a career path known as academic inbreeding. This practice is believed to contribute to academic isolation and diminish the potential for innovation. Nevertheless, the impact of academic inbreeding on the productivity of early-career scientists remains insufficiently studied.

Victoria Slepyh, Junior Research Fellow at the HSE Laboratory for University Development, examined the career trajectories of 1,132 Russian scientists who earned their PhDs in 2012 in the fields of physics, biology, chemistry, and mathematics. To assess research productivity, the author analysed publications in international journals, their citation counts, and the presence of articles in first-quartile (Q1) journals.

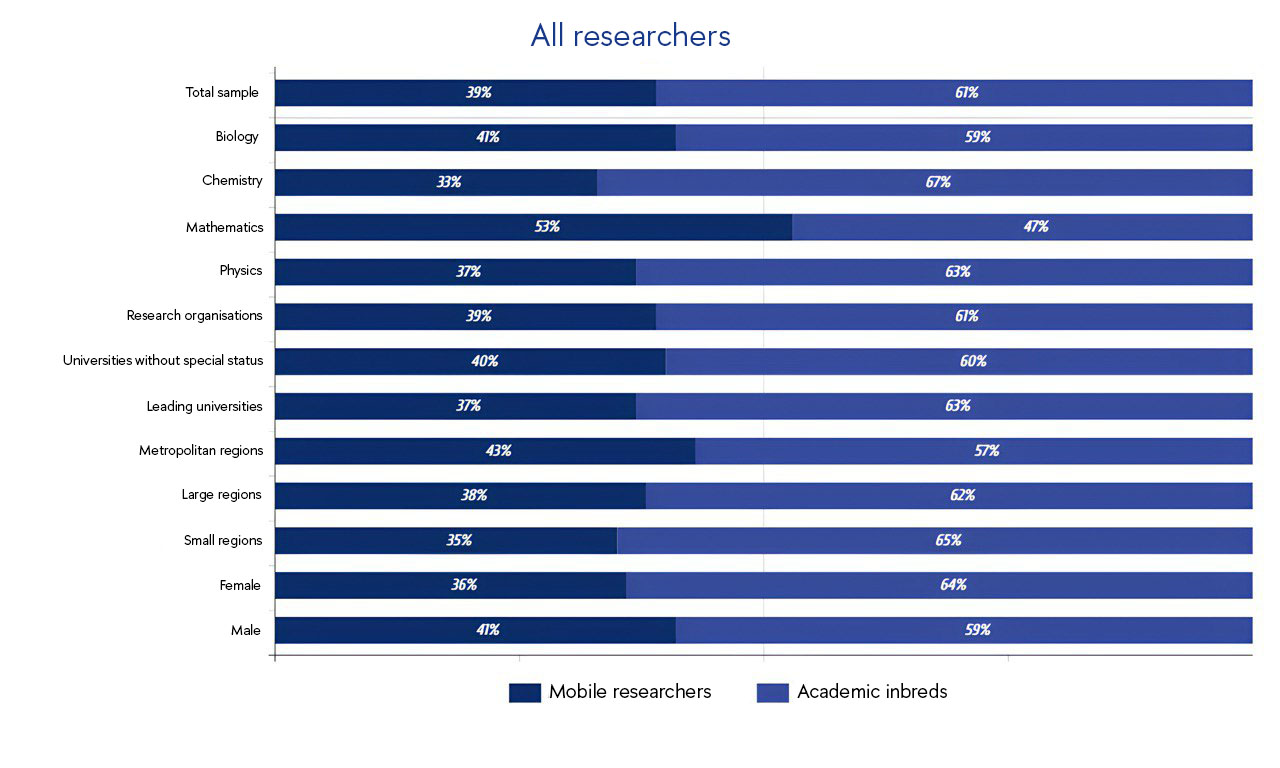

The analysis was conducted on two levels. First, the author examined all 1,132 PhD holders who remained in academia during the first eight years following their dissertation defence. Among this group, the rate of academic inbreeding was 61%. The results showed that graduates who moved to different universities after earning their degrees were, on average, more likely to publish, have articles accepted in prestigious journals, and receive higher citation counts compared to those who remained at their alma mater.

The most pronounced negative effect of academic inbreeding was observed at universities without special status—those not designated as federal or national research universities and not participating in government science support programmes. Early-career researchers at such universities published, on average, 34% fewer articles indexed by Scopus, and their likelihood of having at least one publication in a prestigious journal was nearly half that of more mobile scientists.

According to the author, if an early-career researcher remains at a university with limited scientific activity and resources, they tend to reproduce low academic standards. Moreover, a limited professional experience reduces their competitiveness compared to their more mobile colleagues.

'In prestigious, research-oriented institutions, academic inbreeding generally does not have a significant impact on productivity. This can be attributed to a rich professional environment, including a strong research team, modern equipment, stable collaborations with other organisations, and involvement in major projects,' explains Slepykh.

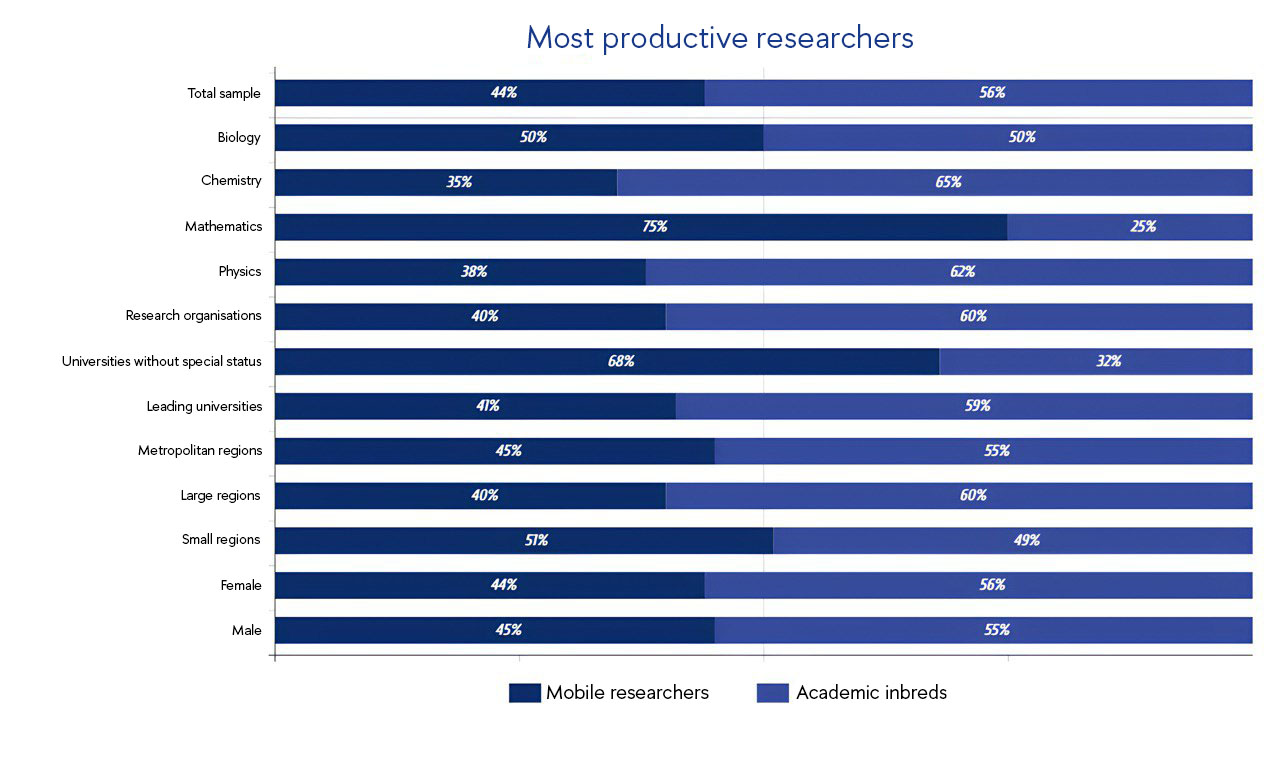

Next, the author identified a subgroup of the most productive scientists—417 individuals whose number of publications exceeded the median (ranging from four to six publications during the first eight years of their academic careers). The proportion of inbreds was 56% in this sample. At the same time, the impact of academic inbreeding on productivity within this subgroup was minimal and appeared only in certain cases—specifically, among graduates who earned their degrees in regions with a saturated academic employment market.

In regions with numerous scientific institutions, graduates have greater opportunities to move to a different employer. When remaining at one’s alma mater under such circumstances stems from inertia rather than a deliberate choice, early-career researchers may miss the opportunity to thrive in a more suitable professional environment. In less developed regions, academic inbreeding is typically driven by limited alternatives. The study findings support the hypothesis that when early-career scientists have more employment options, remaining at their alma mater can negatively affect their productivity.

Additionally, the study revealed differences in behaviour across scientific disciplines. For example, mathematicians were more likely to pursue mobile career paths and less likely to remain at the universities where they earned their degrees, whereas physicists and chemists exhibited a stronger tendency toward academic inbreeding. The author attributes these differences to the nature of research infrastructure and publication traditions in various scientific fields.

'Academic inbreeding, in itself, is not necessarily problematic. However, its consequences can adversely affect scientific productivity, especially at universities without special status or with limited resources. To mitigate the risks of isolation, measures should be implemented to encourage academic mobility and the expansion of external collaborations. These may include internships, academic exchanges, and the development of partnerships with leading research centres. Such initiatives will enhance not only productivity but also the overall quality of the academic environment,' according to Slepykh.

See also:

Scientists Test Asymmetry Between Matter and Antimatter

An international team, including scientists from HSE University, has collected and analysed data from dozens of experiments on charm mixing—the process in which an unstable charm meson oscillates between its particle and antiparticle states. These oscillations were observed only four times per thousand decays, fully consistent with the predictions of the Standard Model. This indicates that no signs of new physics have yet been detected in these processes, and if unknown particles do exist, they are likely too heavy to be observed with current equipment. The paper has been published in Physical Review D.

HSE Scientists Reveal What Drives Public Trust in Science

Researchers at HSE ISSEK have analysed the level of trust in scientific knowledge in Russian society and the factors shaping attitudes and perceptions. It was found that trust in science depends more on everyday experience, social expectations, and the perceived promises of science than on objective knowledge. The article has been published in Universe of Russia.

Scientists Uncover Why Consumers Are Reluctant to Pay for Sugar-Free Products

Researchers at the HSE Institute for Cognitive Neuroscience have investigated how 'sugar-free' labelling affects consumers’ willingness to pay for such products. It was found that the label has little impact on the products’ appeal due to a trade-off between sweetness and healthiness: on the one hand, the label can deter consumers by implying an inferior taste, while on the other, it signals potential health benefits. The study findings have been published in Frontiers in Nutrition.

HSE Psycholinguists Launch Digital Tool to Spot Dyslexia in Children

Specialists from HSE University's Centre for Language and Brain have introduced LexiMetr, a new digital tool for diagnosing dyslexia in primary school students. This is the first standardised application in Russia that enables fast and reliable assessment of children’s reading skills to identify dyslexia or the risk of developing it. The application is available on the RuStore platform and runs on Android tablets.

Physicists Propose New Mechanism to Enhance Superconductivity with 'Quantum Glue'

A team of researchers, including scientists from HSE MIEM, has demonstrated that defects in a material can enhance, rather than hinder, superconductivity. This occurs through interaction between defective and cleaner regions, which creates a 'quantum glue'—a uniform component that binds distinct superconducting regions into a single network. Calculations confirm that this mechanism could aid in developing superconductors that operate at higher temperatures. The study has been published in Communications Physics.

Neural Network Trained to Predict Crises in Russian Stock Market

Economists from HSE University have developed a neural network model that can predict the onset of a short-term stock market crisis with over 83% accuracy, one day in advance. The model performs well even on complex, imbalanced data and incorporates not only economic indicators but also investor sentiment. The paper by Tamara Teplova, Maksim Fayzulin, and Aleksei Kurkin from the Centre for Financial Research and Data Analytics at the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences has been published in Socio-Economic Planning Sciences.

Larger Groups of Students Use AI More Effectively in Learning

Researchers at the Institute of Education and the Faculty of Economic Sciences at HSE University have studied what factors determine the success of student group projects when they are completed with the help of artificial intelligence (AI). Their findings suggest that, in addition to the knowledge level of the team members, the size of the group also plays a significant role—the larger it is, the more efficient the process becomes. The study was published in Innovations in Education and Teaching International.

New Models for Studying Diseases: From Petri Dishes to Organs-on-a-Chip

Biologists from HSE University, in collaboration with researchers from the Kulakov National Medical Research Centre for Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Perinatology, have used advanced microfluidic technologies to study preeclampsia—one of the most dangerous pregnancy complications, posing serious risks to the life and health of both mother and child. In a paper published in BioChip Journal, the researchers review modern cellular models—including advanced placenta-on-a-chip technologies—that offer deeper insights into the mechanisms of the disorder and support the development of effective treatments.

Using Two Cryptocurrencies Enhances Volatility Forecasting

Researchers from the HSE Faculty of Economic Sciences have found that Bitcoin price volatility can be effectively predicted using Ethereum, the second-most popular cryptocurrency. Incorporating Ethereum into a predictive model reduces the forecast error to 23%, outperforming neural networks and other complex algorithms. The article has been published in Applied Econometrics.

Administrative Staff Are Crucial to University Efficiency—But Only in Teaching-Oriented Institutions

An international team of researchers, including scholars from HSE University, has analysed how the number of non-academic staff affects a university’s performance. The study found that the outcome depends on the institution’s profile: in research universities, the share of administrative and support staff has no effect on efficiency, whereas in teaching-oriented universities, there is a positive correlation. The findings have been published in Applied Economics.